Surviving the Spiral: The Internet's Collective Future

From AI appropriation to browsers that evade monetization, the foundations of the Internet teeter

The central contradiction of the AI boom is that if major LLM providers reach the scale they’re pacing for, it’s unlikely to herald a glorious future of networked open web creation. Instead, as creators without significant capital work to escape the gravity well of AI-fueled appropriation, we’ll find ourselves flung back into the past.

I’ve written about this phenomenon of temporal regression in the context of traditional news organizations, but as many leaders of the digital economy move toward a rather nihilistic profit capture, odds are it’s coming for your corner of the web, too.

This is the story of how we’re enshittifying ‘enshittification’ itself, and how we can fight it. If Cory Doctorow's “digital word of the year” describes capitalism eroding the value of entrenched services over time, then my argument is about degraded services being recycled unto themselves and pushing out organic invention.

Once-innovative businesses feeding on their own customers until nothing of value remains is, of course, nothing new.

Once upon a time, the Sears catalog laid the groundwork for modern Internet commerce in… the 1890s. Starting as a mail order exclusive storefront, “The Great Book of Bargains” offered a central place for people in far-flung corners of the U.S. to conveniently purchase curated staples. On the back of government subsidies that drastically cut shipping costs, Sears was an economic colossus by the time it opened its first department stores.

Their proposition to early customers was simple: “We solicit honest criticism more than orders," according to an excellent 2017 piece from Smithsonian Magazine. Large scale mail order shopping was new, so the catalog had to establish itself as trustworthy. If something goes wrong, the shopper could be assured, just give us a call and we’ll set you right.

As Sears expanded, however, they thrust themselves into fights against workers rights movements, attracted a nationwide boycott from civil rights activists, and worked hard to protect their white male corporate hierarchy from the ascendance of women in the workplace. Finally, in late-stage Sears, the most profitable remaining piece of their business was predatory store credit cards whose prey was their own shrinking customer base.

Sears, in short, became great by exploring new horizons, and died as a jealous rent-seeker.

Reflecting on what happened to Sears, I can’t help but see parallels to the open web we’re building now. This time, though, we’re collapsing more than local economies and mall real estate – it’s the very threads that connect us in written digital community that we unravel. This time, there is no central entity’s heir spiraling us toward purposeless oblivion. Instead, pulled and shorn by tidal forces masquerading as phenomena beyond our control, we’re all spiraling together.

Since you’ve forgiven my tendency for poetry, I’ll put it plainly now: The Internet that people from low-resource languages experience today is coming for the rest of us. Vice has an excellent summary of a new arXiv paper from Brian Thompson et. al on the proliferation of low-quality machine translated content on the Internet.

“The vast majority [of content] came from articles that we characterized as low quality, requiring little or no expertise or advance effort to create, on topics like being taken more seriously at work, being careful about your choices, six tips for new boat owners, deciding to be happy, etc.”

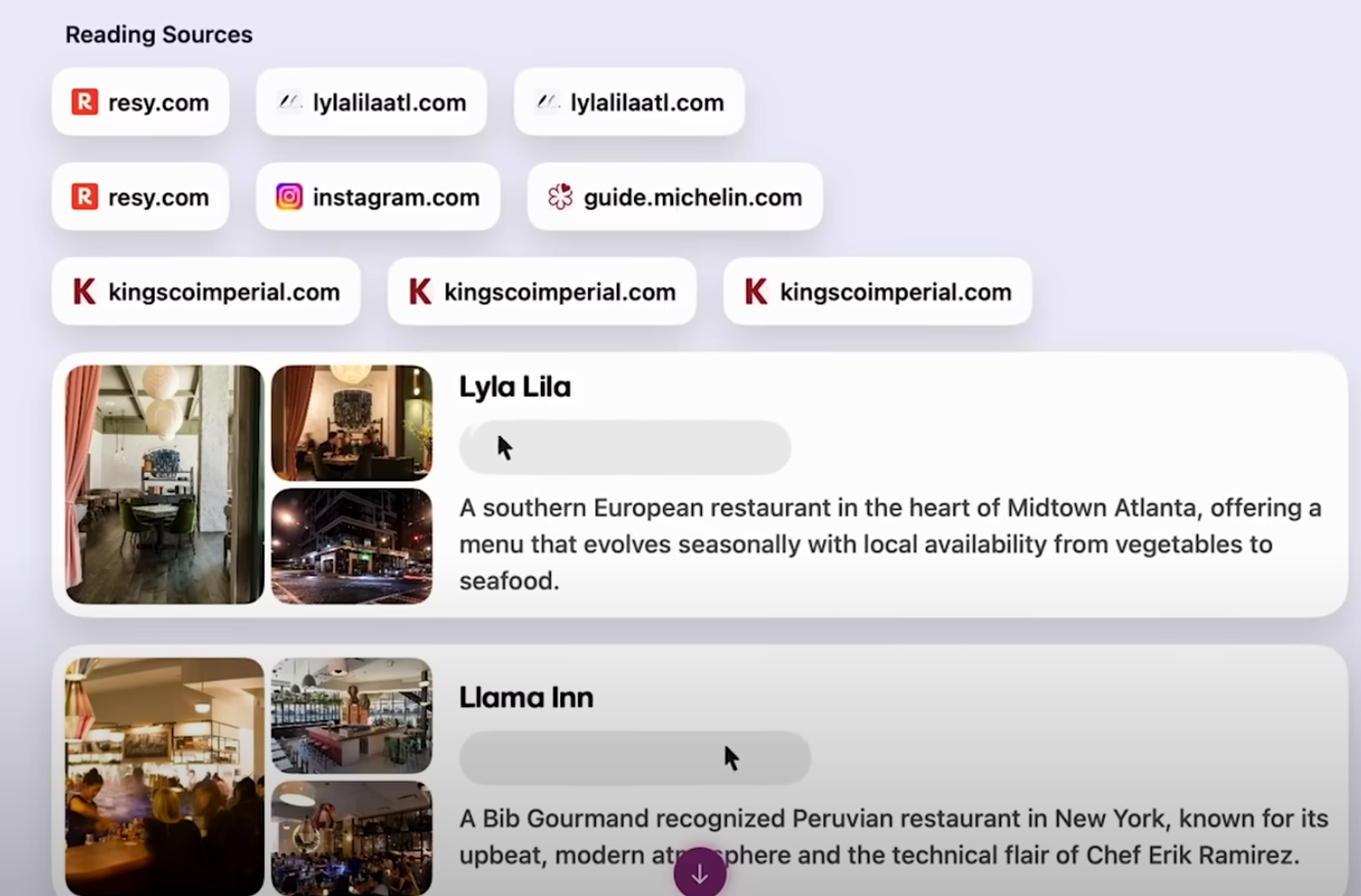

Here on the English-language Internet, the startup The Browser Company recently previewed an upcoming product that “browses the web for you.” In the words of Engadget:

“Arc Explore, which the company says should be ready for testing in the next couple of months, uses LLMs to try and collapse the browser, search engine and site into a singular experience.”

This idea, I want to be clear, is brilliant. I’ve long believed that software should trend toward a single multi-purpose surface akin to a workbench, where a combination of tools and an operational blank page allows efficient work across the entire scope of a single project.

I can’t help but suspect, however, that the execution of this idea is self-defeating. In practice, what Arc Explore proposes is to remix the sum total of tooling and creation on the open web into a single surface under its own control by way of an AI-powered agent that fulfills your requests.

Sounds great! Except that Arc doesn’t make any money. Even if the Explore model were to succeed and proliferate across products, what could it teach us about maintaining a sustainable ecosystem? So, the best case launch scenario for Explore may starve creators of the resources they need to create – little things like ad space, subscription models and affiliate revenue.

Arc has a smart response to increasingly ineffective search engines like Google’s. But underneath the SEO optimized and AI-copied drek cluttering your results is a more fundamental challenge for the modern Internet. Why should I create high-quality artifacts outside of a walled garden social network? It’s one thing to do it for free, but entirely another when I won’t even have the chance to help people remember who I am.

The implicit bargain of the open web — that if I provide information, the right people might learn where to find me or maybe even who I am — erodes. Private social networks, then, are uniquely incentivized to promote an information source, rendering increasing volumes of new information undiscoverable to AI applications. Arc is a great diagnosis of the problem, but when it comes to the treatment? Doctor, heal thyself.

Forgive this pessimism from someone who believes in the potential of AI, but I can’t escape a growing sense that what we’re building now isn’t as new or innovative as we gas ourselves up to believe. Instead, we may be doing little more than creating a new class of meta rent-seekers.

Let’s think of it this way: As far back as 2010, consumers had soured on Facebook. As it captured an enormous sum of the media economy, its privacy policy ‘eroded’ as it led the charge to normalize late-stage Sears level customer service. All the while, content moderators across the industry, exposed to traumatizing content for years on-end, are often treated like shit-shoveling servants.

And yet, we don’t imagine the customer service will get better – we aren’t building toward that. And when it comes to content moderation, we aren’t talking about professionalization. We’ve already heard self-serving justifications for getting rid of it altogether: We’re traumatizing people, It's inefficient! So instead, a heavy-handed AI will do all of the modding, and oops, as a consequence, we must limit human expression to fit within the precise boundaries of what we’re willing to invest in building. (i.e. algospeak on TikTok and ‘v*ccines’ on Threads)

Yes, the profits look amazing, but so would the major car companies if customers had to inspect their own vehicles off the line. When you compare the regulatory differences between much of the Internet marketplace and the physical one, whatever we’re trying to build here doesn’t look as impressive as it seems.

Here, it becomes apparent how we’re enshittifying the enshittification itself: In the past if you wanted to run a content mill, you’d hire an underemployed person willing to churn out cheap summations of their knowledge. After that, networks might incentivise creators to churn out content with rebranded stipends or the lure of possibly winning a full-time job. And after that, you might just hire someone from wherever you can find the cheapest English speaking labor to do some artful plagiarism. Now, you wouldn’t even bother with all that: Just recycle your SEO term through an LLM and post it in dozens of different formats across your spoof sites.

I don’t mean to condemn everyone’s individual business decisions here. My intention is to offer a clear eyed look at the economy we’re building all of our beautiful AI projects to support.

Under our foundations is a bed of sand.

Government action, like regulation or new support for the information economy, is probably the clearest answer to the foundational economic problems here. However, a tradeoff has been made pretty explicit in Washington: The entire world is competing on these grounds, and the nature of the economic terminus of pre-AGI AI tech is unknown. So, it's plausibly in everyone’s interest that regulations don’t hamstring American AI development to the benefit of a world power that is apparently constructing an all-consuming party loyalty based sci-fi dystopia.

And so, we watch this generation of the open web being scuttled for LLM parts. The future of the next open web, if we can keep it in any culturally-meaningful sense, should look a lot like the old Internet. We’ll find a series of small, curated spaces put together by elite institutions or nerd collectives meant to speed the flow of independent and trustworthy information. You might have to submit 50 applications to have your website listed everywhere it needs to be. In short, it’s Federation, like Mastodon. Community is a force of preservation that self-interested power has no means to break.

That’s right, you heard it here first: Web portals are coming back, baby! Non-community based methods of curation have been demonstrated to collapse in subsequent generations under the weight of corporate capture. (My co-editor reminds me that the endurance of Reddit is a good example of this idea.)

My advice for all of the independent content producers out there: It would be a mistake to cave and endlessly supply the LLM machine without remuneration in some attempt at public service. [Note to self: Block GPT from scraping MoP – Erica]

I ask you to resist the implied conclusion of Open AI’s legal arguments against The New York Times, that thanks to fair-use standards, LLM producers are some anointed class with special rights to participate in capitalism, while the rest of us must feed their machine for the sake of humankind.

There are creative ways that this can be resolved prior to a collapse in the information economy. My colleague Erica Greene outlined one of them recently in this very newsletter. But in the event LLM producers aren’t compelled into joining this kind of compromise, we still don’t have to accept the idea of an entirely consolidated information marketplace.

Even if the darkest vision of the LLM revolution comes to pass, we already know that all of this is cyclical. If creatives are about to embark on a wilderness journey, running one step ahead of the AI replication maw, we would be better off conserving as many resources as we can before we fade into the treeline.

Comments

Sign in or become a Machines on Paper member to join the conversation.

Just enter your email below to get a log in link.